Deepening Surveillance: The Intricate Web of Spies in eSwatini’s Parliament

Amid political unrest in eSwatini, the kingdom under King Mswati III exhibits a complex network of espionage within its legislative body. Recently, the spotlight has turned to the monarchy’s strategic placement of loyalists and spies in parliament, a move that underscores the pervasive control exerted by the absolute monarch over the political discourse in the kingdom.

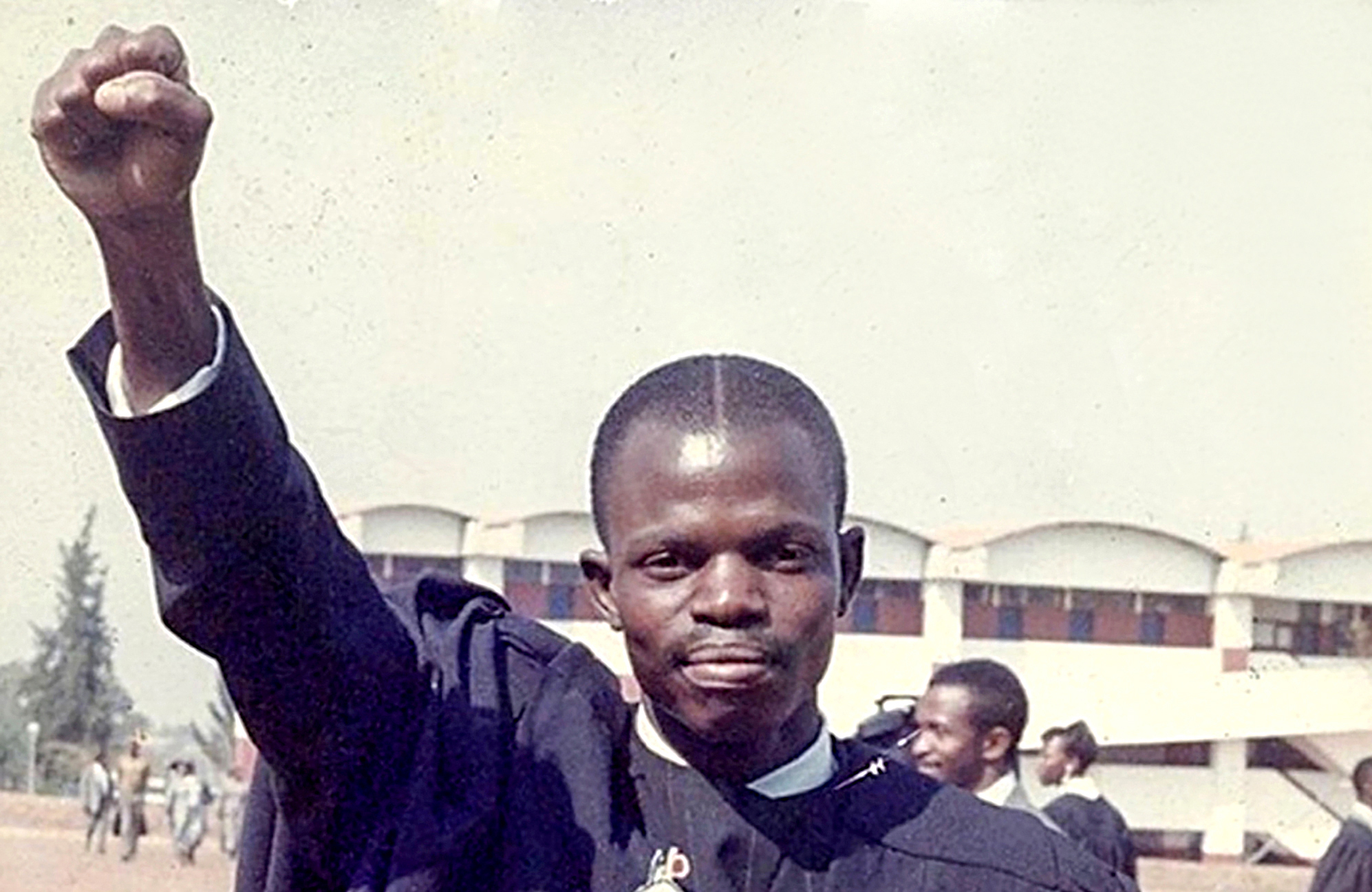

The disclosure of this espionage network follows the politically charged convictions of pro-democracy MPs Bacede Mabuza and Mthandeni Dube, who were sentenced to life imprisonment on terrorism charges, a situation that has ignited international concern over human rights in eSwatini. Sources indicate that figures such as Prince Lindani, former Army Commander Lieutenant General Tsembeni Magongo, and others are implicated as central figures in this surveillance apparatus.

Prince Lindani, noted for his military background, along with other appointed officials, reportedly play key roles in monitoring parliamentary members, especially those inclined towards democratic reforms. This system of surveillance is meticulously structured so that spies operate without clear knowledge of each other’s activities, ensuring that even the spies themselves remain under scrutiny.

The operations of this intelligence network are not solely aimed at stifling political dissent but also at gathering information on social and economic sentiments among the populace. This dual approach aims to fortify the monarchy’s grip on power by preemptively managing and mitigating any potential upheavals that could arise from within the ranks of the government or the general populace.

However, criticism of these practices is mounting. Wandile Dludlu, Deputy President of the People’s United Democratic Movement (PUDEMO), argues that the parliamentary system under King Mswati is manipulated to serve not the interests of the people, but those of the royal family. According to Dludlu, the appointment of spies is a calculated strategy to ensure the monarchy’s interests are safeguarded against the rising tide of democratic aspirations.

The government’s stance, as articulated by King Mswati’s spokesperson Percy Simelane, denies the deployment of spies in parliament, suggesting instead that the monarch has access to parliamentary debates through recordings, thus obviating the need for direct surveillance. This assertion, however, does little to assuage concerns about the lack of transparency and the suppression of political freedoms under Mswati’s rule.

As eSwatini continues to grapple with these issues, the international community remains watchful. The strategic use of intelligence within parliament reflects broader tensions between the enduring practices of absolute monarchy and the growing demands for democratic governance in the kingdom. The situation in eSwatini serves as a critical case study of how traditional power structures adapt to modern political challenges, often at the cost of civil liberties and democratic development.